Help wanted: Must enjoy 'a million sunrises and sunsets' (and clear a big hurdle)

Published in Business News

PORT TOWNSEND, Washington — Above the ruckus of the ferry's car deck, the chattering of passengers pressed up against windows and the thrum of engines, Adam Knutsen watched the sea unfold from a place few ever get to stand.

The "bridge," where the ferry's captain and other high-ranking officers are stationed, was quiet. Windows stretched across the space, wrapping the vessel's navigational brain in blue daylight. Knutsen's eyes flitted from the horizon to a small radar screen. The waters here are notoriously busy and require a careful eye. Pleasure boats dart across the ferry's path, crab pots dot the edges and tidal currents throw off departure times.

"Let's do a departure whistle," Knutsen called over to the navigational expert seated next to him. One long foghorn ripped across the inlet.

One day, the 22-year-old hopes this will be routine, part of his daily responsibilities as a licensed officer. For now, he's in the final year of the Washington State Ferries apprenticeship program, shadowing every role onboard.

Launched in 2024, the apprenticeship was created to both diversify and replenish the ferry workforce, and to remove two major barriers: time and cost.

"Entering into this industry, you're going to have to invest a minimum of three years at least to get a basic license, and then $40,000, to get close to being on the bridge of a boat," said Emily Hopkins, director of the West Coast campus of the Maritime Institute of Technology & Graduate Studies (MITAGS), a maritime school in Seattle.

This pathway changes that. The program pays for training, with no prior maritime experience required. Among roughly two dozen apprentices, 40% identify as women or people of color. But spots are scarce: Out of hundreds of applicants, only 12 for each cohort are accepted.

If people wanted to advance before this program, they had to "figure it out" in terms of time and funding, said Jay Moritz, operations advanced training program manager at the WSF.

"I'm not kidding," said Moritz. "That was the system."

Over two years, the dozen selected apprentices are fast-tracked toward earning a mate's license, a supervisory credential that opens the door to higher pay and advancement.

Those selected start at MITAGS, where they alternate between classroom instruction and ferry placements. Weeks of coursework in emergency response, maritime law and navigation are followed by hands-on rotations on the ferry.

Knutsen first heard about the program from his uncle. At the time, he was working in IT for the city of Poulsbo, where he grew up. If not for the pandemic, he says, he probably would have gone straight into an engineering degree. But after two years of Zoom classes during high school, he was burned out.

"I just couldn't imagine going straight into college," he said.

Ferries had always been a part of his childhood. He'd ferry over to Mariners games with his dad and brother, where he'd get to gaze out from the curved windows. The apprenticeship offered him a clear alternative: "It gives me an education, allows me to get into a good industry, and I don't have to worry about debt hanging over my head."

Once Knutsen graduates next year, he'll have to line up for a position as a mate. The hierarchy on a ship is strictly seniority-based, so he'll start at the lower levels and advance when positions become available. Once he's working as a mate, though, he'll make a decent wage. The starting salary for mates is between $97,000 to $110,000 a year.

The idea for the program came from Steve Nevey, head of the ferry system. He started his career as a mariner and rose through the ranks in a similar apprenticeship model in the United Kingdom. When he arrived at WSF in 2022, he noticed a shortage of workers "right off the bat."

But it wasn't among entry-level positions. It was among the higher ranks, jobs that required copious amounts of mentorship and training before people could assume them.

"Every other maritime organization I've worked at, they have a big group of young people that they can point to and say, 'That's our future captains,'" said Nevey. "We didn't have that."

Within a few months, he'd pitched the apprenticeship and two other programs meant to boost the credentials of people already working within the ferry system: the "A/B to mate" program and the pilotage program. These are fast-tracked programs that take under a year to complete.

As a result of all these efforts, the ferries have now effectively matched hiring with their retirement rate. Next, the system is focused on creating programs to recruit more engineers to work on the ferries.

While the apprentice program is an easier path than before, it can still be a financial squeeze. Apprentices are paid about $200 a day only for the 360 days they are out at sea, amounting to around $36,000 a year for each of the program's two years.

Some participants are staying with family or leaning on partners while they're in training. They must also be prepared to commute long distances to where they are stationed to work, or to attend class in Seattle, depending on where they live.

But they are taking the challenges in stride.

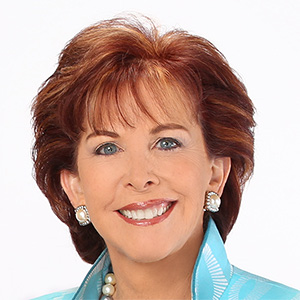

Montanan Chloe Belle, 28, said she'd bounced among several jobs before joining the second apprentice cohort. She wanted a job that would pay well, and where she could work with her hands.

"I can't really do computer work. I hate computers. I can't stand them," she said.

Since she joined, she's fallen for the culture and the views. "There's always a minute to peek over the side or look through a window. The sunsets, the sunrises, the San Juans — they're just unparalleled."

Classes at MITAGS in Seattle have also taken her through maritime terminology, knowledge that she says makes her feel like a "pirate."

Her classmate Malinda Poirier was a preschool teacher and stay-at-home mom for years before starting the program. As her kids grew up, she started thinking about her own future.

"I always knew this would be my time to shine," she said. Her love of ferries started young — one of her earliest memories was taking one down from Alaska when her family moved to Snohomish County. "It felt like a very easy decision, because I was having such a hard time deciding what I wanted to do."

Back at the bridge, Captain Jesse Rongo, who supervises Knutsen aboard the Kennewick, gently asked Knutsen to guess the approximate distance from the ferry to other vessels in the water.

"I think it's fantastic," Rongo said of the program. "It gives young people in the community a strong union job and a career they can grow into."

The views aren't bad either. "If you looked through a sailor's photo album," he added, "it's just a million sunrises and sunsets."

Later that day, Knutsen traded the bridge for the car deck. Wearing a high-vis vest, he stood by the loading ramp as the vehicles — a production truck, a few sedans, a cluster of motorcycles — pulled forward. He motioned each one into place.

It's far from the bridge. But for Knutsen and others in the program, it's worth the wait.

©2025 The Seattle Times. Visit seattletimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments