Alaska Air's year of expansion will bring the world closer to Seattle

Published in Business News

Last December, Alaska Air Group executive Ryan St. John said the SeaTac-headquartered airline had reached an “inflection point” in its 90-plus-year history.

Alaska had recently completed its $1.9 billion acquisition of Hawaiian Airlines, the second time the company had bought another mainline air carrier in less than a decade. With the Hawaiian deal finalized, Alaska was embarking on an ambitious three-year push that would include new routes, a premium credit card and an aggressive drive to compete with the giants of its industry.

Now, a year past St. John's inflection point," what that push means for Seattle and for the airline is coming into focus. Seattle travelers will be able to more easily reach destinations in Europe and Asia as Alaska announces new nonstop routes, and its competitors respond with their own new flights.

Delta, the second-largest carrier at Seattle-Tacoma International Airport, has already introduced new international routes from Seattle, including one that competes directly with Alaska's new destinations.

The Hawaiian acquisition was key to Alaska's expansion plan. Along with the brand, Alaska inherited Hawaiian’s fleet of larger planes, skill set and equipment that allow the airline to transition from a domestic carrier dominating the Seattle market to a global airline making a push beyond its West Coast hub.

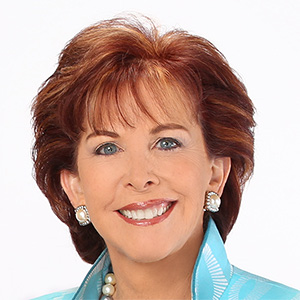

Alaska, led by CEO Ben Minicucci since spring 2021, has so far stuck to its timeline for integrating Hawaiian's operations into its own. It announced five new long-haul routes from Seattle to destinations in Asia and Europe, launched a joint loyalty program for Alaska and Hawaiian customers and saw customer sign-ups for the new Atmos premium credit card exceed Alaska’s year-end goal in just two weeks, the company said.

But Alaska also faced disruptions that threatened its operational and financial vision. Some were industrywide, like a slump in demand this spring and the federal government shutdown this fall. Others were unique to Alaska, like two tech outages that grounded their fleet for hours at a time and led to hundreds of flight cancellations.

In early December, Alaska lowered its financial expectations for the year, warning investors those setbacks lost the company $80 million in the fourth quarter of the year. Still, Alaska executives are optimistic about their plan to grow beyond Seattle dominance and, fueled by that expansion, boost its profit by an additional $1 billion and reach $10 earnings per share by 2027.

Airline analysts largely share Alaska's confidence in its ambition to become a global carrier.

“2025 was a noisy year for the industry writ large,” said Tom Fitzgerald, an analyst with TD Cowen. “It clouded a lot of progress (Alaska) made and a lot of really good momentum they have … in the things they can control.”

Clark Johns, a director with Alton Aviation Consultancy, agreed Alaska was “still well-positioned” to meet its three-year goals. In a strategic move, Johns continued, the airline is “focusing on where they have historical strengths,” and building from there.

Eash Sundaram, an aerospace industry venture capitalist and former JetBlue executive, said the changes can only mean good things for customers. More competition usually means lower prices. "It's going to be exciting for people in Seattle," Sundaram said.

A year of change

Alaska unveiled its plan to capitalize on its Hawaiian acquisition in December 2024, at the end of a trying year. In January 2024, a panel flew off an Alaska Airlines 737 MAX shortly after it took off from Portland, Ore., leaving a gaping hole in the side of the plane at 16,000 feet in the air.

The harrowing incident mostly affected Boeing and its supplier Spirit AeroSystems, as safety regulators worked to understand how the plane had been delivered to Alaska without four bolts meant to hold the panel in place.

But Alaska was a party to the investigation, participated in regulatory hearings scrutinizing what went wrong and faced lawsuits from passengers who accused the airline of failing to ensure the plane was safe. Those lawsuits, on hold for most of 2024 and into 2025 as the National Transportation Safety Board completed its investigation, will ramp up in 2026.

This year, with the panel incident mostly behind them, Alaska focused on its expansion. It received regulatory permission to operate Alaska and Hawaiian as one airline in the eyes of the regulator.

Next year, it will launch a single booking system and continue negotiations to finalize joint contracts for its unionized workforce. It will also start service for three of the long-haul routes it announced this year, and introduce a new livery on its Boeing 787 fleet.

“We have launched as much change at Alaska this year … as we have in any year I’ve been there,” Chief Financial Officer Shane Tackett told investors at a conference earlier this month. “It’s going to be really fun to now just focus on running a high-quality core airline again.”

“We’re going to have to get better at doing it every day,” he continued. “But I think we can compete with anybody.”

There’s a limit to how much any airline can grow domestically, and Alaska was approaching the threshold, said Savanthi Syth, an analyst from financial firm Raymond James. It was clear to industry watchers that Alaska would make a play to expand internationally in the next five to 10 years.

Acquiring Hawaiian Airlines sped up that timeline. So far, it is going well, Syth said, but cautioned it is still very early days.

“There’s some smart choices that have been made, but it's easy to make money in the summer,” she said. “We’ll see what happens in the winter.”

‘Fierce competition’

Alaska is the fifth-largest carrier in the nation, accounting for about 6% of airline travel from October 2024 to September 2025, according to the Bureau of Transportation Statistics. Hawaiian is the 10th largest carrier, capturing a little less than 2% of the market.

Combining both those networks still leaves the joint carrier significantly behind the nation’s four largest airlines. Delta and American each claim slightly more than 17% of the market share, while Southwest and United each capture 16%.

In its hometown, though, Alaska Air Group accounts for 52% of travelers moving through Sea-Tac Airport, according to data from the Port of Seattle. Alaska Air Group includes Alaska, Hawaiian, regional carrier Horizon Air and ground support company McGee Air Services.

Delta trails behind with 24% market share at Sea-Tac. United captures about 5% while Southwest accounts for 4%.

Alaska has dominated Seattle travel but it had one “obvious gap,” as Fitzgerald puts it. It didn't offer Trans-Pacific flights on its own planes, Fitzgerald said, acknowledging that Alaska does participate in the Oneworld Alliance, which gives Alaska customers the ability to tap into other airlines' international flights.

Adding Hawaiian Airlines into the mix created a “1+1=3” situation, Fitzgerald said. “It opens up a lot of things you can do.”

Through the acquisition, Alaska inherited Hawaiian’s Boeing 787 Dreamliners and Airbus A330s, widebody planes that can reach destinations the airline couldn’t reach with its 737 MAX fleet. It also took over Hawaiian’s existing order for more 787s.

But it is still much smaller than its competitors. Alaska, Hawaiian and Horizon together operate about 400 aircraft while Delta's fleet totals more than 930 planes.

The Hawaiian acquisition, then, allows Alaska to expand in a way that wouldn’t be possible for an airline to do on its own, said Sundaram, the former JetBlue executive. It’s simply too expensive to buy a new fleet of widebody aircraft and sell tickets at a price comparable to other large carriers already flying similar routes.

As Alaska expands, Sundaram expects Delta will make another play to capture more of Seattle’s customer base.

Delta fought aggressively a decade ago to gain more market share in Seattle, making Sea-Tac a West Coast hub with new gates and domestic routes to compete directly with Alaska’s flights.

Now, Alaska’s push into Europe especially could force Delta to get back on the offensive, Sundaram said.

“These are markets Delta loves and makes a lot of money" in, he said. “I see in the next 12 to 18 months, there will be fierce competition.”

Delta is already doubling down on Seattle, as the company put it in a June news release announcing two new lounges at Sea-Tac and nonstop routes to Barcelona and Rome. Alaska had announced its nonstop route from Seattle to Rome earlier that month.

“Delta’s commitment runs deep in Seattle,” Delta President Glen Hauenstein said in the announcement. “We’re investing in what matters most to our customers — exceptional, premium experiences — and reinforcing our role as Seattle’s largest global carrier.”

Hauenstein is retiring in February, after 20 years with the airline and nearly a decade as its president.

Some turbulence

Even with plans to add at least 12 new long-haul routes from Seattle by 2030, analysts don’t fear Alaska will grow too big, too quickly. The airline is adding its new routes strategically, the analysts said, redeploying its acquired arsenal of aircraft rather than placing a large order to buy new planes.

“It’s a pretty measured expansion,” Fitzgerald from TD Cowen said. “It’s not a management team that’s known for deploying irrational capacity. They’re very conservative, very measured.”

Alaska also has the strategic advantage of inheriting Hawaiian’s skill set, Sundaram said. It will have a gentler learning curve and fewer costs associated with training and equipment.

Similarly, the analysts don’t expect Alaska’s IT troubles will have a lasting impact on the airline.

When choosing a flight, customers ultimately look at price and rarely factor in a past travel mishap, like an IT outage.

Three IT incidents — a July outage caused by a hardware failure in one of Alaska’s data centers, an October outage also caused by Alaska’s systems and a Microsoft network outage that same month — cost the company nearly $70 million, according to estimates from Alaska and Syth.

Alaska hired consulting firm Accenture to review its IT infrastructure after the second incident and, so far, has not found any systemic architecture failures, Tackett told investors at the recent conference.

Syth worried the hiccups this year may have pushed Alaska slightly off-course from its profitability goal. But, she continued, the company isn’t far off and has time to catch back up.

Johns, from Alton Aviation Consultancy, said Alaska’s biggest challenges next year will be macro factors, things that are out of their control: consumer demand fluctuations. High fuel prices on the West Coast. And, aircraft manufacturers’ ability to deliver aircraft orders on time.

Of Alaska Air Group’s three-year profitability goal, Johns said, “time will tell."

"It’s certainly an ambitious target," he said, but from what I’ve seen, they view it's executable.”

©2025 The Seattle Times. Visit seattletimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments