Former Illinois Gov. George Ryan, who halted state's death penalty but was imprisoned for corruption, dies at 91

Published in News & Features

CHICAGO — George Homer Ryan served one term as Illinois governor, his scandal-clouded tenure and subsequent imprisonment on federal corruption charges overshadowing a nationally historic move to halt the state’s death penalty and empty its Death Row amid concerns of widespread misconduct in capital cases.

Ryan, a Republican whose 35-year public career spanned from local Kankakee County Board chairman, state legislator, Illinois House speaker, lieutenant governor, secretary of state and ultimately Illinois’ 39th governor from 1999 to 2003, died Friday in a hospice in his hometown of Kankakee, said former Illinois House GOP leader Jim Durkin. Ryan was 91.

Ryan’s career was honed on old-school politics, reliant upon patronage and deal-making, as he also underwent an ideological metamorphosis that took him from hard-line rural conservatism to more pragmatic progressive policymaking. Such was the case in moving from a capital punishment supporter to placing a moratorium on the death penalty.

Ryan’s bona fides as a conservative had been such that Republican Gov. James R. Thompson selected him as his running mate in 1982, believing he needed Ryan’s conservative credentials to balance his own liberalism in seeking reelection.

As House speaker in 1982, Ryan single-handedly blocked the legislature from voting to enact the Equal Rights Amendment to the federal constitution and he steadfastly opposed abortion. By 2000, as governor, he vetoed legislation that would have banned taxpayer-funded abortions for poor women whose health was jeopardized by their pregnancy.

After announcing he would not seek reelection in 2001, with a scandal engulfing his governorship, Ryan asked lawmakers to guarantee gay rights in public accommodations.

“As I have said before, I favor equal and fair treatment for everyone, regardless of who they are as a person,” Ryan wrote to lawmakers. “I have never been in favor of special treatment for anybody, but I have always been in favor of fairness for everybody.”

That prompted then-state Sen. Patrick O’Malley of Palos Park, who already had prepared a GOP run for governor, to declare: “This appears to continue to go against the very things he has historically been associated with.”

Ultimately, it was the federal investigation of Ryan’s political and governmental operation called Operation Safe Road and its initial probe of commercial drivers’ licenses exchanged for bribes in his secretary of state’s office that proved Ryan’s undoing as governor. Public support evaporated and he announced he would not seek reelection. He was indicted in December 2003, less than a year after leaving office.

Ryan could display a gruff external demeanor, which was only accented by his deep bass voice. It came in handy as the last speaker of the “Big House” — before the Cutback Amendment reduced the size of the chamber to 118 from 177 — when running the state House was a political chore likened to herding cats.

“But all that gruffness was just kind of baloney,” said Durkin, who served in the House during Ryan’s tenure as secretary of state and governor. “He wasn’t a person that took himself too seriously. He was approachable, fun-loving. He was really a down-to-earth guy who wanted to help people.”

Durkin said Ryan wouldn’t survive as a politician in today’s political climate because he wanted to get things done, even if it meant compromises had to be made.

“George was a guy that wanted good things for Illinois. He wore Illinois on his sleeve. He had this incredible ability to be able to bridge the gap between the bitter partisanship between Democrats and Republicans. And he also was able to bridge a gap between the differences between labor and management, something that is very unique.”

Ryan’s successes as governor in moving his agenda through the General Assembly was a reflection that he was a creature of the legislative process and the give-and-take that went with it, said Ryan’s predecessor as chief executive, former Gov. Jim Edgar.

“He didn’t get hung up on ideology, like some of us probably did, but he just kind of wanted to work after the deal. Sometimes they were good deals. Sometimes they weren’t good deals, but there was always a deal,” Edgar said.

“He had as many friends among the Democrats as he did the Republicans,” said Edgar, who earlier in his career served a term in the House with Ryan, who Edgar said was likely better suited to the legislative branch than the executive branch.

Former Democratic Illinois Senate President John Cullerton, who served in the legislature from 1979 to 2020, said of the seven governors he dealt with, Ryan was the best in dealing with the legislature.

“George, given the fact that he was a speaker and a governor, it gave him a unique position to understand the legislature,” Cullerton said. “He probably had the most volunteer floor leaders in the legislature willing to push his agenda of any governor in the history of the state.”

Cullerton’s predecessor as Senate president, Democrat Emil Jones Jr., recalled that he and Ryan used to shoot pool together as young lawmakers in Springfield and the bond between them grew. One example was Ryan’s approval of the earned income tax credit for low-income families, backed by Jones and sponsored by an up-and-coming South Side state senator named Barack Obama, who would go on to be president.

“We were friends,” Jones said of Ryan. “That’s how we got many things done.”

Ryan was born in Maquoketa, Iowa, and grew up in Kankakee. After serving in the U.S. Army in Korea in 1954, he came back to work in his pharmacist father’s drug stores, turning them into a small successful chain. In 1956, Ryan married Lura Lynn Lowe, whom he had met in high school.

A back room in Ryan’s Kankakee pharmacy served as a hub for local Republican political activities and he was mentored by the powerful GOP county chairman and state legislator, Ed McBroom. People looking for state jobs had to get McBroom’s approval–and sometimes buy a vehicle from his car dealership if they got hired or got a pay raise.

In 1962, Ryan ran McBroom’s campaign for the state Senate; in 1968, Ryan was appointed to the Kankakee County Board; by 1971 he had become County Board chairman and was off to the legislature the next year and became House speaker a decade later.

After serving as Thompson’s lieutenant governor for eight years, Ryan ran and won two terms as secretary of state when Jim Edgar gave up the office to make a successful bid for governor. After Edgar left the governorship following two terms, Ryan ran to replace him, winning the office while often campaigning to the left of former downstate Democratic congressman Glenn Poshard.

Ryan’s lengthy tenure in Springfield and willingness to engage in horse-trading to get his agenda made him popular with lawmakers in both parties. Having served previously as House speaker, as a Republican he had a successful relationship with powerful Democratic Speaker Michael Madigan.

His ability to forge friendships and alliances worked for him early on, when he secured passage of a massive, $12 billion Illinois FIRST capital improvement spending program to reconstruct schools, roads, bridges, highways and sewers.

As governor, Ryan also mediated a $3.5 billion aid package for the coal industry, a bill of rights for HMO patients, tighter regulation of factory hog farms, $1.5 billion more in school funding, health insurance for 125,000 additional kids from low income families and added 30,000 acres of open space.

In October 1999, Ryan made a much-ballyhooed trip to Cuba and was feted by Fidel Castro as the governor bucked U.S. policy and urged the nation to reopen trade with the communist island country.

As governor, Ryan had authorized only one execution to proceed and had exhibited emotional qualms about the power of the death penalty even though there was no doubt about the convicted man’s guilt.

On Jan. 31, 2000, Ryan declared a moratorium on imposing the death penalty in Illinois, noting that since the state reinstated capital punishment in 1977, 12 people had been executed while another 13 had been exonerated.

“Until I can be sure that everyone sentenced to death in Illinois is truly guilty, until I can be sure with moral certainty that no innocent man or woman is facing a lethal injection, no one will meet that fate,” Ryan said.

He cited a Tribune investigative series that examined each of the state’s nearly 300 capital cases that exposed how bias, error and incompetence had undermined many of them.

Ryan’s moratorium was continued by his successors but it wasn’t until a decade after he issued it that Illinois lawmakers approved a law abolishing the death penalty, which was signed by Democratic Gov. Pat Quinn.

Ultimately, with only days remaining in his term, Ryan in early 2003 commuted the sentences of 167 Death Row inmates and pardoned four others — the largest such commutation in U.S. history. He was repeatedly nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize.

In many ways the simplest of men, Ryan’s Death Row decision added a dimension of complexity to his otherwise straightforward legacy.

“Who the hell am I,” he said in speeches on the death penalty, “to say that a man should die?”

In September of 2020, Ryan co-authored with former Tribune reporter Maurice Possley the book, “Until I Could Be Sure: How I Stopped the Death Penalty in Illinois,” detailing Ryan’s internal deliberations on the death penalty and discussing the national movement to abolish it.

Critics charged Ryan’s Death Row moratorium was a desperate effort to deflect attention from the scandal that had enveloped his administration. Supporters said Ryan was filled with genuine moral angst over a system that made quite real the possibility of sending an innocent person to their death.

It was during his tenure as Illinois secretary of state that his troubles with the law began.

As secretary of state, his campaign coffers were regularly loaded with money from his employees, who were compelled to sell tickets for Ryan fundraisers. Commercial driver’s licenses were for sale, and among the unqualified motorists who paid for his license was a truck driver named Ricardo Guzman.

In 1994, part of the taillight assembly on Guzman’s truck fell off onto Interstate 94 near Milwaukee. A minivan driven by Rev. Duane Willis and carrying his wife and six children hit the dropped part. The van exploded into flames and the children, aged six weeks to 11 years, were all killed.

Known in shorthand as the “licenses for bribes” scandal, 75 people were convicted of various infractions as a result of the probe; 30 of them were employees of the secretary of state’s office.

During a six-month trial, Ryan was defended, without being charged legal fees, by a high-powered legal team from Winston & Strawn, the law firm headed by former Gov. Thompson. Despite a defense put together by former U.S. Attorney Dan Webb at an estimated cost of $20 million, a jury found Ryan guilty of all 18 counts against him in April 2006. Also found guilty was Ryan’s co-defendant and close friend, lobbyist Lawrence Warner, who made more than $3 million on insider deals.

Ryan became the third Illinois governor to be convicted of wrongdoing since the 1970s. Otto Kerner received 3 years in prison in 1973 for taking bribes while governor in the late 1960s; he was paroled after serving a year. Dan Walker was sentenced in 1987 to 7 years for bank fraud unrelated to his public duties but was released after 17 1/2 months.

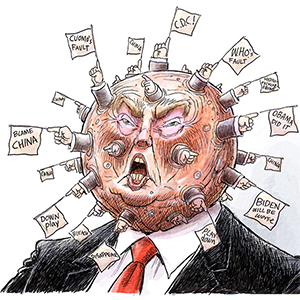

Ryan’s successor, Democrat Rod Blagojevich, was impeached, removed from office and convicted of federal corruption charges. He was sentenced to 14 years in prison but was granted clemency by President Donald Trump after serving eight years. Trump pardoned Blagojevich earlier this year.

Throughout Ryan’s federal investigation and trial, he was steadfast in declaring he had done nothing wrong. At his sentencing, he relented a bit, saying of residents, “When they elected me governor of this state, they expected better, and I let them down, and for that I apologize.”

Ryan’s wife, Lura Lynn, died in Kankakee on June 27, 2011. Ryan had been allowed out of prison in Terre Haute, Indiana, to be with her when she died. He was released from a federal prison in Indiana in January 2013, serving the final months of his term in home confinement at his home in Kankakee.

“I think we should remember George Ryan for the good things he’s done in his life, because he’s done a lot of good things for Illinois,” Durkin said. “Everybody makes mistakes. Everyone. And George paid the price but he also handled it like a man and moved on.”

The Ryans had six children: five daughters including a set of triplets — Julie, Joanne, Jeanette, Lynda and Nancy — and one son, George Homer Ryan Jr.

_____

(Chicago Tribune reporter Ray Long contributed to this story.)

_____

©2025 Chicago Tribune. Visit at chicagotribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments