Leaked contract shows how Cuba pockets money Bahamas pays for medical services

Published in News & Features

The Bahamian government appears to have signed off on a contract that directs most of the money paid for the services of four Cuban health professionals to a Cuban government entity while giving away its legal authority on key issues to the communist-ruled island, according to a copy obtained by a group monitoring Havana’s medical missions abroad.

Bolstering the United States’ allegations of unfair labor practices in Cuba’s government-run medical missions, the 2023 contract required the Bahamian Ministry of Health and Wellness to pay $22,000 in monthly fees for the four workers’ services directly to the Cuban state company Comercializadora de Servicios Médicos Cubanos, or Trading Company of Cuba’s Medical Services.

But the four workers themselves — two medical specialists advisers, one computer sciences engineer and a health data specialist — only received a monthly allowance between $990 and $1,200, for a total cost of $4,380, paid directly to them by Bahamian health authorities. Those stipends hover around the country’s minimum salary of $250 per week and were deemed enough to cover rent in the expensive islands, which The Bahamas did not provide for the Cuban workers.

The leaked contract was published by Cuba Archive, a Miami-based nonprofit group that monitors Cuba’s medical missions. The U.S. State Department has used the group’s work to put together its annual human trafficking report. Last year, the State Department celebrated the group’s director, María Werlau, as one of “outstanding individuals around the world who are fighting to end human trafficking.”

‘Forced labor’

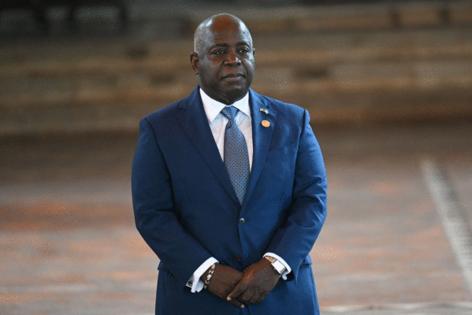

The Miami Herald has not independently verified the contents of the contract, which appeared to bear the signature of Bahamian Health Minister Michael Darville. The one-year contract appeared to have been signed in Havana in 2023, but the month and day were left blank in the copy obtained by Cuba Archive, which Werlau believes indicates the agreement is still in place. Four copies of the documents were signed.

While Cuba has promoted the medical brigades as a show of solidarity with other nations, the health workers have become a major source of foreign revenue in recent years. The purported agreement with The Bahamas had Cuba receiving between 84% and 92% of the money the Bahamas paid for the services of the Cuban workers. The Cuban state company also collected 50% of the overtime and bonuses paid by The Bahamas to the Cuban staffers.

Since 2020, the State Department has kept Cuba on the blacklist of countries that do not do enough to fight human trafficking and has cited the Cuban medical missions as an example of “forced labor.” Defectors from those missions have said their Cuban handlers confiscate their passports, limit their movements and pressure them to do political work on behalf of the Cuban government.

Recently, Secretary of State Marco Rubio expanded visa restrictions on Cuban officials involved with the medical missions to also apply to third-country officials contracting those services. That measure has created friction between U.S. and Caribbean leaders, many of whom have come to rely on Cuban doctors to fill critical gaps in their health care systems.

‘Concerns’

The leaked document has added even more tensions ahead of a visit by Bahamas Prime Minister Philip Davis to Washington. He is expected to be among seven Caribbean leaders meeting with State Department officials on Tuesday, and the Cuban medical brigade is among the topics expected to come up alongside discussions about countering illegal immigration, drugs and firearm trafficking, disaster relief and border security.

Bahamian officials have not disputed the contract’s authenticity.

Davis, who previously acknowledged that “a portion” of the salaries of the Cuban doctors is sent to a Cuban agency, told reporters last month after the leak that he was speaking to the Cuban government about the “concerns.”

Bahamian Foreign Minister Fred Mitchell, responded by questioning the motivations behind the leak of the contract, which he said could be part of a broader effort to influence Bahamian public policy and undermine national sovereignty.

“The Bahamas government does not engage in any practice contrary to international labor norms. Let’s make that abundantly clear,” Mitchell said. He told lawmakers the government must resist forming policy based on “subjective interpretations of untested material.”

The Herald reached out to Darville and Mitchell. Mitchell said his comments were in the public domain and he had nothing more to add. Darville did not respond to a request for comment about whether Cuban professionals were indeed getting less than 20% of the funds the government was paying on their behalf and other legal details in the leaked contract.

In March, Darville told the Nassau Guardian newspaper that two ophthalmologists, one retina specialist, one cataract specialist and one optometrist from Cuba are in the country. He also said there are three nurses and other support staff from Cuba.

At the time, Darville said The Bahamas’ Foreign Affairs Ministry was involved in ongoing negotiations with the U.S. over its concerns about the medical brigade, which some Caribbean leaders think were settled during Rubio’s recent visit to Jamaica when the matter was raised with others in the region.

“The services they provide in the country (are) needed, and so the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is presently back and forth with their counterparts in the United States ... because they want more clarity on what we are doing with these workers, because it seems as if there is this cloud that (there) is forced labor, and we don’t believe so,” Darville told the paper.

A month later, he traveled to Havana, where he met with Cuban Public Health Minister José Angel Portal to discuss their 20-year cooperation and the expansion of Cuba’s medical services in The Bahamas.

“During the dialogue, the ministers will discuss new strategies to expand specialized care in priority areas such as ophthalmology, orthopedics, cardiology and oncology, identified as sectors with growing demand,” Cuban state outlet Cubadebate reported about the April 19 meeting.

The Trading Company of Cuba’s Medical Services is the Health Ministry’s firm in charge of exporting medical services and selling health tourism packages. Its affiliation with the ministry is public knowledge.

While Caribbean governments have pushed back on Rubio’s assertion that the medical brigade program is a form of “forced labor,” the contract signed by The Bahamas reinforces the notion and shows that the relationship is lopsided and favors Cuba.

Withdrawing doctors

Not only did Bahamian authorities sign away rights to discipline the professionals, leaving it in the hands of the Cuban state agency. They also let Cuba off the hook if any legal disagreement arises, according to a contract provision giving the Cuban government discretion about whether to comply with Bahamian laws.

In case of disagreement, the law applicable to the contract is that of The Bahamas, the document says, but with a big caveat: “provided that such legislation and its effects do not contravene the principles of the social, economic and political system of the Republic of Cuba.”

The Cuban entity also had the power to withdraw the doctors at any time, the document shows. And if The Bahamas were to agree to U.S. requests to move away from the current contract to negotiate better terms for the Cuban doctors, the language in the document would still make The Bahamas liable for payments to the Cuban government.

The Cuban government seems to have planned specifically for this scenario. The document includes language that would make the Bahamian government still liable for its obligations under the agreement in the face of “any provisions, regulations, proclamations, orders or actions... of foreign governments to the parties or others that in any way prevent or attempt to prevent... the complete performance of this agreement.”

At least two other Caribbean governments that employ Cuban medical professionals say they do not have the same terms as the ones in The Bahamas’ contract. However, because contracts are not made public, the claims cannot be independently verified. The Bahamas agreement includes a confidentiality provision prohibiting the disclosure of its details for two years after its completion.

Werlau told the Herald that it is not enough for governments to arrange to pay doctors in these missions directly, because Cuban authorities have concocted other schemes to confiscate most of the money. For example, in 2012, the head of a Cuban official educational mission in The Bahamas, another type of service offered by the Cuban government to other countries, sent an email detailing how the Cuban teachers were supposed to collect the salaries paid directly by Bahamian authorities and wire most of it back to Cuban authorities on the island.

Werlau said his organization had developed screening guidelines for foreign officials and human rights groups to discern whether Cuban doctors have been trafficked and urged foreign officials to publish the contracts.

If other nations need Cuban doctors, she said, “they should hire them directly, as they do with any other foreign doctor who comes to practice in their country. They should pay them directly. The doctors should be able to bring their families. They should not be subject to all these restrictions through an intermediary that is a dictatorship.”

_____

©2025 Miami Herald. Visit miamiherald.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments