See how this museum is preserving a fragile piece of American history

Published in Lifestyles

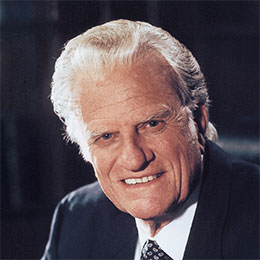

KANSAS CITY, Mo. -- Holly Messinger, the textiles conservator at The Arabia Steamboat Museum, carefully laid out the pieces of a frock coat, an 1850’s relic recovered from the bottom of the Missouri River.

“I am working on a frock coat that I took out of the freezer about a month ago,” Messinger said. “It’s been frozen for 35 years,” she explained. “It just looked kind of like a lump of hamburger.”

The fragile wool-cotton blend men’s coat is now a challenging puzzle for Messinger, a bench-trainer conservator and life-long seamstress, who says she is working in her dream job preserving clothing from a bygone era.

“Cotton fiber does not do well in water, so this coat is actually much more fragile than many of the things that I’ve worked on,” Messinger said. “This is the kind of coat we don’t currently have on display because it is a wool cotton blend.”

Most of the restored clothing currently on display at the museum is 100 percent wool.

The story of the coat’s recovery is as captivating as its preservation.

In September 1856, the three-year-old, 171-foot long Steamboat Arabia, laden with over 200 tons of cargo bound for 16 frontier towns, struck a tree snag and quickly sank to the bottom of the Missouri River, just six miles west of Kansas City.

Over the years, the Missouri River shifted its course, leaving the Arabia and its valuable cargo buried 45 feet beneath a Kansas cornfield.

In 1988, The Steamboat Arabia was excavated by a team led by Bob Hawley and his sons, David and Greg Hawley, along with friend Jerry Mackey and restaurateur David Luttrell.

The ship and its cargo, buried in mud, didn’t see light nor oxygen for over 132 years, leaving many of the pre-Civil War artifacts well preserved. Among the cargo were crates of china, tools, shoes, and textiles, including coats, hats, pants, and bolts of fabric—including silk fabric.

Messinger’s work at the museum, which was established in 1991 to house the recovered treasures, is a delicate balance between science and artistry.

A trip to the freezer led to the project Messinger was working on last week. “When I found these coats, they were wet and muddy,” she said.

“They were packed in crates, but the crates were not watertight and the original cotton thread disintegrated,” Messinger explained. “By the time I found them in the freezer, there were three coats folded together.”

The frozen coats were carefully thawed in a water bath and gently separated. After drying, Messinger meticulously cleans the artifacts with delicate animal-hair brushes and painstakingly removes rust, fleck by fleck, with a dental pick.

“The challenge is figuring out what each piece can take and how far I can go with it,” she said.

Messinger was trying something new and explained how she would preserve and reassemble a black wool-over-cotton man’s overcoat.

“We’re mounting this section of fabric from a recovered coat on a nylon mesh fabric to give it some stability, and then I’m going to go around the edges with a consolidating adhesive that will keep it from turning to powder,” she described.

To replace the disintegrated wood buttons on some restored coats, the museum has in-house digital printing technology allowed them to produce nearly identical versions of the original buttons.

Even with new technologies, Messinger said that much of her work in identifying the fabrics and dyes used is about using her expertise, combined with touch and simple microscope.

The key with preservation she said is to never do something to an artifact that cannot be undone in the future.

In the preservation lab, where visitors observe ongoing conservation efforts, Messinger and other preservationists continue to clean and conserve the artifacts.

Even as the frock coat takes shape, the immense task of cleaning and preserving the vast remaining collection continues. Messinger said she will work 100 hours to reconstruct this one frock coat for display.

The museum’s collection, ranging from fine china and carpentry tools to children’s toys and the world’s oldest pickles, offers a unique window into American history.

Ultimately, Messinger’s dedication is about more than just preserving fabric; it is about preserving stories.

“To actually have my hands on these very old things and see how they go together, and also sort of feel the lineage between myself as a modern dressmaker and tailor and the people who made these, is a very intimate process,” she said.

It is a connection to the past, a narrative woven in threads of time, rescued from the depths of the Missouri River.

©2025 The Kansas City Star. Visit kansascity.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC. ©2025 The Kansas City Star. Visit at kansascity.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments