As this Seattle Asian grocery weathers Trump's tariffs, shoppers brace for higher prices

Published in Business News

Uwajimaya, the Seattle-based Asian grocer, has navigated hardship before.

Not long after the family business opened its doors in 1928, it temporarily shuttered when founders Fujimatsu and Sadako Moriguchi and several of their children were incarcerated at a Japanese detention camp during World War II.

More recently, the COVID-19 pandemic strained the grocery industry's supply chain, forcing Uwajimaya, among others, to raise prices.

Now, President Donald Trump's rapidly shifting approach to tariffs and trade deals is causing a wave of economic uncertainty for the store chain that is likely to leave its customers feeling the pinch. The levies are just one more factor affecting grocery prices.

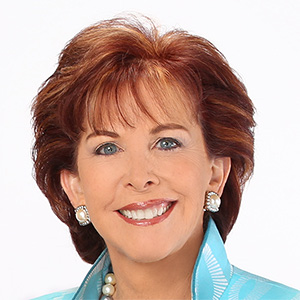

With distributor and grocery margins where they are, it cannot all be absorbed by the distributors and the retailers," said Uwajimaya's president and CEO Denise Moriguchi. "For sure, it will be felt by everyone."

Last month, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics tracked an uptick in inflation in the Seattle-Tacoma-Bellevue area of Washington, with regional costs jumping 2.7% year over year. The upswing was partially attributed to tariffs.

However, news of potential price increases at Uwajimaya isn't scaring off some of its loyal customers. Seattle resident Sara Louie, 29, said prices are skyrocketing across industries. "Everything is expensive anyways," Louie said.

It's giving others pause. Kelcie Lei Asuncion, a 34-year-old Seattle resident, said she'll be paying more attention to tariff-related hikes.

But "will it dissuade me from going to Uwajimaya more?" she said. "Not right now."

"What will happen next?"

At Uwajimaya, not all items will see the same price hikes because of the tariffs, Moriguchi explained. Some may only see an increase of a few cents.

With these changes, Uwajimaya is searching for product alternatives to alleviate the burden on its patrons. Moriguchi said her team is also ensuring that customers have a range of choices.

Her company primarily works with distributors who import on Uwajimaya's behalf, though its wholesale division has also started to feel the effects of tariffs.

With the exception of meat, Uwajimaya imports the majority of its inventory from around the world. Moriguchi estimates that over 50% of its grocery items, such as sauces and canned goods, come from Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand, Vietnam and China.

Its seafood selection is sourced both domestically and from Asian countries, while its produce is imported from Mexico and South American nations.

The U.S. and Japan recently agreed to a deal that leaves the Asian ally with a 15% tariff on imports, instead of the original 25% levy. The American and Chinese governments made a short-term agreement in May that brought "reciprocal" tariffs down to 10% from 125%.

Trump is pushing for a 30% tariff on imports from Mexico beginning next month, though negotiations are underway.

In anticipation of these tariffs hitting, Uwajimaya's distributors initially stockpiled some products. But they're now passing the costs of the tariffs on to the grocery chain.

"When there's been price increases, it's the distributor that's kind of seeing the hit of the tariff," Moriguchi said. "We're just starting to see some of that."

The impact is staggered because the tariffs aren't implemented all at once, Moriguchi added. Trump's erratic trade strategy has included imposing tariffs, then opting to either pause them, reverse course, increase the levies or decrease them based on the country involved.

Meanwhile, some of the grocery industry's volatility is precedented, Moriguchi said, as produce prices tend to yo-yo based on harvest conditions.

Still, "Uwajimaya's profitability falls within typical grocery ranges," she added. "We've had some strong years and not-as-strong years over the past decade but are in a healthy place and here to stay."

National grocery chains share Moriguchi's broader concerns about economic instability.

Kroger, owner of QFC and Fred Meyer, reported last month that, in the first quarter of 2025, its total company sales dropped slightly, to $45.1 billion from $45.3 billion in the same quarter a year ago. The company plans to close 60 stores over the next year and a half.

"While first quarter sales and profitability exceeded our expectations, the macroeconomic environment remains uncertain," Kroger chief financial officer David Kennerley said then in a written statement.

Kroger declined to comment for this story.

Tariffs are not the sole pressure on grocery businesses, but they are an added challenge on top of other hurdles like the rising costs of insurance, health care and other expenses related to labor.

Moriguchi anxiously awaits the tariffs' full force, saying, "It does keep me up at night, thinking, 'Oh gosh, what will happen next?'"

"We are local"

Moriguchi persists in carrying out her grandfather Fujimatsu's vision. He emigrated from Matsuyama, Japan, to Tacoma in the 1920s. Originally, he sold fishcakes and other wares to the area's Japanese laborers.

Uwajimaya is named after Uwajima, the Japanese city where he learned to make fishcakes.

Once Moriguchi's elders were released from the incarceration camp, they moved to Seattle and reopened their business in the Chinatown International District. Uwajimaya's flagship store has remained there for around eight decades.

With fewer Asian markets back then, there wasn't as much competition — and there was less interest among the general population, Moriguchi said.

That's changed in recent years. Uwajimaya has expanded beyond its flagship location, with stores in Bellevue and Renton, Washington, and a new store planned for Issaquah, Washington. Another location is across state lines in Beaverton, Oregon.

Today, even traditional American grocery chains maintain large selections of Asian specialty items, and customers can buy their favorites online, Moriguchi said.

H Mart, an Asian supermarket chain based in New Jersey, operates 10 stores in Washington, including four in Seattle. The company didn't respond to requests for comment.

Uwajimaya stands out among other grocers as one run by the third generation of the founding family. The company employs just under 500 people.

"We are local," Moriguchi said. "We're active in different ways that I think some of the companies that aren't based here can't be."

Proceeding with caution

Nearing a century in business, Uwajimaya has carved its niche in the community — and in the hearts of Seattle-area residents.

For Louie, the store has been a longtime staple. She remembers childhood times spent grocery shopping for Asian goods with her family at Uwajimaya.

"Chinatown kind of raised me," said Louie, whose grandmother emigrated from China to Seattle, and whose mother is from Hong Kong. "So if it happens to be in Chinatown, like Uwajimaya has been, I will definitely support the local community first and foremost."

Now, as an adult, Louie frequents Uwajimaya weekly to stock up on soy sauce, oyster sauce and chili oil. She also peruses the Asian trinkets.

"I can spend hours at Uwajimaya," Louie said.

Rising costs encourage her to shift her focus from restaurants to home cooking.

"Budgeting would be in consideration, but that means eating out less and cooking more at home," Louie said. "Buying fresh groceries is important because health is still wealth."

Sheyla Cerda, 29, goes to Uwajimaya once a week to buy fresh sushi, meat and vegetables and stop by the food court.

As a resident of the Capitol Hill neighborhood, she said other nearby grocers don't offer the same parking setup. Cerda also believes Uwajimaya's produce selection is superior.

"Their produce has been not the cheapest compared to other grocery stores," Cerda said, "but that's because their quality is really, really good."

She originally hails from the Mexican city of Guadalajara, which is home to a large Asian population. There, Cerda learned how to make a few Asian dishes.

Once she moved to Seattle, her Filipina roommate introduced her to Uwajimaya. Cerda said she'll likely have to cut back on buying more expensive fruits, but she'll keep shopping there, despite the tariffs.

Still, Asuncion is moving forward with caution. She stops by Uwajimaya on a monthly basis. She's familiar with Japanese culture because she was born in Hawaii and lived in Orange County, California, which has numerous Japanese markets.

Asuncion's local friends recommended Uwajimaya after she moved to Seattle in 2019. Though the brand only offers a few goods from the Philippines — Asuncion is of Filipina ancestry — she shops there for Japanese and Hawaiian groceries.

"I always note prices, even before the tariffs starting," she said. "I haven't really been hit by it yet, but I feel like, in the future, I will take more note.

©2025 The Seattle Times. Visit seattletimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments