Love dinosaurs? Here's what makes Central Valley a fossil hotspot

Published in News & Features

SACRAMENTO, Calif. — In 1936, a Central Valley teenager made an incredible discovery.

Gustine High School student Allan Bennison dug up the fossilized remains of a hadrosaurus — a duck-billed dinosaur that lived in North America during the Late Cretaceous Period, The Fresno Bee reported in 2013.

The bones, which Bennison found in Del Puerto Canyon in Stanislaus County, represented the first scientifically documented discovery of a dinosaur fossil in California.

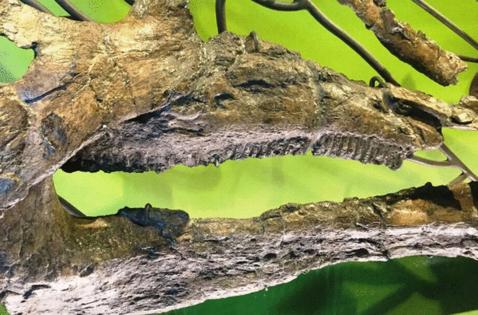

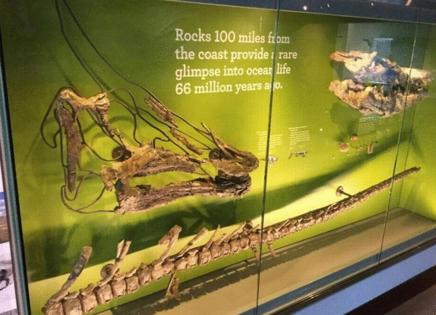

About a year later, Bennison found the preserved skull and spine of a mosasaur in the foothills west of Gustine, according to previous reporting by The Fresno Bee and The West Side Index.

The ancient marine reptile was later named Plotosourus bennisoni in Bennison’s honor.

”Most paleontological finds are done by amateur fossil hunters and even just regular people,” said Michael George, lead paleontologist at the Fossil Discovery Center of Madera County in Chowchilla. “It’s because of people’s interest in this field that we as paleontologists can work on more and more fossils every day.”

According to George, the Central Valley is home to a number of significant fossil finds — including California’s state dinosaur.

—Why is Central Valley a good place to find dinosaur fossils?

“Most people see the Central Valley as all agriculture and flat lands,” George said, but it’s a rich source of prehistoric treasures.

During the Mesozoic Era, a period spanning approximately 252 to 66 million years ago that’s known as the “Age of Reptiles,” “Most of California was underwater,” George said. “This is why we find so many prehistoric ocean animals, like mosasaurs, ammonites, clams of all kinds and even megalodon teeth in California.”

In addition, George said, the fossils of “mega fauna from the Ice Age are present throughout a vast majority of the Central Valley,” including mammoths, dire wolves, saber-tooth cats, camels and ground sloths.

While conditions in the Golden State weren’t ideal for the preservation of dinosaur fossils, “There have been a few dinosaurs found in California,” George said.

The majority of the dinosaur fossils discovered in California belong to hadrosaurs, which lived during the Late Cretaceous period approximately up to 66 million years ago. The large, land-dwelling plant eaters had duck-like beaks and broad muzzles.

“These herbivorous dinosaurs thrived in what was once a coastal plain environment,” said California Curated, a website dedicated to science and discovery in the Golden State. “Their remains have been uncovered primarily in areas that were once submerged by ancient seas, such as parts of the San Diego Formation.“

Other dinosaur fossils found in California include Aletopelta coombsi, a kind of ankylosaur lived in the Late Crectaceous period in what is now Southern California, George said.

The armor-coated herbivore likely had large spikes on its shoulders and a bony tail club.

Construction workers unearthed a partial A. coombsi skeleton near Carlsbad in 1987, according to Smithsonian magazine.

—California state dinosaur found in Fresno County

One of the most significant fossil finds in the Central Valley was Augustynolophus morrisi, which roamed California about 66 million years ago.

A member of the hadrosaur family, the duck-billed dinosaur measured about 26 feet long and weighed about 3 tons, according to the California State Capitol Museum.

Only two fossil specimens of A. morrisi have ever been found, The Fresno Bee reported in 2017, excavated from layers of rock that once lay at the bottom of the ancient Pacific Ocean.

Both sets of bones were discovered in the Panoche Hills west of Interstate 5: the first in Fresno County in 1939 and the second in San Benito County in 1941.

The two specimens can be found at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County.

A. morrisi’s name honors two Californians: philanthropist Gretchen Augustyn and paleontologist William J. Morris.

According to George, paleontologists “can only speculate” about how the dinosaur reached the Central Valley.

“The dinosaur was found in the Moreno Formation, which is more widely known for having prehistoric marine reptiles, such as plesiosaurs and mosasaurs,” he said, adding that “the hadrosaur might have died near the then-coastline and drifted out to sea with the current.”

In 2017, then-Gov. Jerry Brown signed a bill naming Augustynolophus morrisi as California’s official state dinosaur into law.

“The people of Fresno County should be proud that they’re one of the only areas in which bones of this dinosaur have been found,” state Assemblyman Richard Bloom, a Democrat, who authored Assembly Bill 1540, told The Fresno Bee in 2017. “Augustynolophus morrisi is going to do Fresno proud.”

—Where can I see dinosaurs in the Central Valley?

There’s a variety of dinosaur-themed attractions across the Central Valley, ranging from occasional events to permanent exhibits.

On January, the Big Fresno Fair hosted a traveling Dinosaur Adventure event, billed as a “one-of-a-kind exhibit featuring realistic, life-sized dinosaurs that come alive with their life-like movement and roars.”

Fresno’s Chaffee Zoo held an overnight dinosaur-themed event featuring fossil searches on April 12.

Fossils are on display at a number of Central Valley museums, including the Buena Vista Museum of Natural History in Bakersfield.

The Fresno Discovery Center features giant dinosaur sculptures and a variety of hands-on science exhibits, including a section where kids can dig for fossils in the sand.

At the Fossil Discovery Center of Madera County, visitors can learn about the animals that roamed the Central Valley during the Pleistocene epoch 700,00 years ago.

The center is directly across the road from the Fairmead landfill, site of “one of the largest middle-Pleistocene fossil excavations in North America,” the Fossil Discovery Center said on its website.

Exhibits at the Fossil Discovery Center range from the fossil remains of camels, horses, giant sloths and saber-tooth cats to full-scale replicas of a Columbian mammoth and a 12-foot-tall short-faced bear. There’s also a paleontological laboratory that lets visitors how fossils are excavated and preserved.

“Most people would have to go to La Brea Tar Pits (in Los Angeles) to see these ancient creatures,” George said, so being able to spot the remains of prehistoric beasts at the “only fossil museum in the entire Central Valley” is special.

He said the Fossil Discovery Center aims to “inspire the next generation of paleontologists.”

“Like many people my age, I was influenced at a young age by ‘Godzilla’ movies and seeing ‘Jurassic Park’ on the big screen when it came out,” George said. “I remember liking these giant monsters but not knowing there was a profession behind it. Once I heard the term ‘paleontologist’ I knew that was what I wanted to do for the rest of my life.”

Since then, he said, “I have worked with some young students who now have gone on to college and are pursuing their passion to increase the knowledge of paleontology.”

Prehistoric animals’ appeal isn’t limited to children, George added.

“A majority of the time I catch more adults staring in awe at these creatures than kids do,” George said.

—Where can I find fossils in California?

Since fossils are considered a non-renewable resource, “You have to have a special permit if you wish to hunt for fossils legally,” George said.

Fossils cannot be removed from federal or state land without government permission, according to George and the federal Bureau of Land Management.

However, if you manage to find a fossil on private property, “It is technically yours,” George explained.

At The Ernst Quarries in Bakersfield, would-be fossil hunters can pay $15 to $40 to dig in the “bonebed” — primarily for marine fossils such as shark teeth and clams.

The 260-acre property is adjacent to Sharktooth Hill, home to “one of the most significant marine fossil sites in the world,” the Buena Vista Museum of Natural History said on its website.

The Ernst Quarries said it provides visitors with all the tools they need.

“You get to keep everything you find with the exception of scientifically significant fossils,” The Ernst Quarries said on its website. “If you find a skull or articulated assemblage of bones, we keep it and put it in a museum.”

©2025 The Sacramento Bee. Visit sacbee.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments