Seahawks sale could supercharge Paul Allen's causes, but it won't be simple

Published in Business News

Seattle Seahawks fans have been understandably frustrated by the off-again, on-again nature of the sale of the team, which was finally confirmed Wednesday after months of speculation, media reports and denials.

But the secretive, heavily orchestrated process reflects the complexities of hawking a two-time Super Bowl champion widely expected to fetch upward of $7 billion.

For starters, any sale needs approval not only of the team’s current owner, estate of the late Paul Allen, but at least three-quarters of the league’s 31 other owners, a cast of colorful characters with varied agendas.

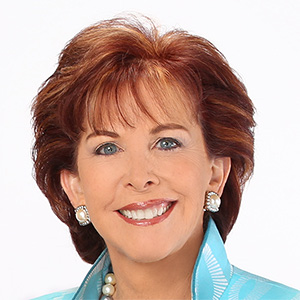

“It’s definitely a different kind of beast when you're (selling) an NFL team,” said Natalie Welch, director of the sport and entertainment masters of business program at Seattle University and an expert in sports economics. “There’s a lot of secrecy, a lot of stuff happening behind closed doors.”

The convoluted process also underscores the huge challenges facing the Allen estate as it steadily converts the late Microsoft co-founder’s vast holdings into funding for his many philanthropic causes.

When Allen died in 2018, his estate was considered to be not only the largest in Washington state history — Forbes put it at $20 billion — but among the most varied and idiosyncratic.

On top of the Seahawks, the Portland Trailblazers and a share of the Seattle Sounders soccer club, Allen had collected everything from waterfront mansions and superyachts to vintage computer equipment and some of the world’s most prestigious works of art.

Long before his death, Allen said he intended to devote much of his fortune to philanthropy. In 2010, he joined other uber-wealthy Americans, including his Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates, in pledging to give away at least half his wealth, then estimated at $13.5 billion.

He launched major philanthropic and community efforts, including the Paul G. Allen Family Foundation, now the Allen Family Philanthropies, the Allen Institute for Brain Science and the Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence, and the Museum of Pop Culture, or MoPOP.

Some of Allen's philanthropy was unconventional, including funding some of his causes through Vulcan, the company he co-owned with sister Jody Allen, which managed ventures ranging from real estate to space travel to museums.

Allen seemed to want to “reinvent” the traditional philanthropic model, said David Callahan, founder and editor of the trade journal Inside Philanthropy. “He was one of these tech guys who wanted to find new ways to do social impact.”

When Allen died at 65 in 2018, from complications related to non-Hodgkin lymphoma, experts warned it could take years or even decades to unwind such a complicated estate.

There would be intricate tax questions around an estate that was heavy on real estate and sports teams. Appraising and marketing so many varied and unique assets would take time and effort.

The estate would also have to carefully manage various ongoing businesses, as well any intellectual property and any international holdings.

All of those things are intensely time-consuming activities," said Jenna Ichikawa, an estate planning attorney and shareholder at Seattle-based Stokes Lawrence who heads up the firm's estate planning group. "It would take a lot of time to handle each of the various assets."

Timing wasn’t always optimal for the sale of some of his assets, as markets were roiled by the pandemic and the short recession that followed.

Allen’s 414-foot superyacht, Octopus, listed for $325 million in 2019, didn’t sell until 2021, after the price had been lowered to $278 million.

In 2022, his estate sold a slew of real estate, including a 120-acre hilltop property in California’s Santa Monica Mountains and eight properties on Mercer Island, including two waterfront mansions, for substantially less than the properties' appraised value or asking prices.

In other areas, however, the estate has done well. A 2022 auction of Allen’s art collection generated a record-breaking $1.5 billion, with many of the pieces bringing more than pre-auction estimates.

The Blazers, which went on the market last year, will be sold to Tom Dundon, the owner of the NHL’s Carolina Hurricanes, for around $4 billion, after being appraised for around $3.5 billion. The sale could close as early as March.

Timing would seem perfect for the sale of Seahawks, following their stellar 2025 season and dominant performance in the Super Bowl.

While the Sports Business Journal puts the team’s market value at “between $6.6 billion and $7 billion,” other analysts say the Super Bowl win, coupled with upcoming negotiations for its media-rights deals, could push the Hawks’ sale price far higher.

Some have even speculated it could beat out the current record for a North American sports franchise – the $10 billion sale of Los Angeles Lakers last year.

Allen bought the team for $194 million in 1997 from Ken Behring.

Allen's purchase of the Seahawks was widely credited with keeping the team in Seattle: Behring had wanted to move the team to Los Angeles after he was unable to renovate the Seattle Kingdome or build a new stadium.

Speculation over prospective buyers has been all over the map, with much attention on the possibility that another Seattle-area individual or group might emerge.

Welch, with Seattle University, cautions that a lot of work likely remains before any sale occurs, including possible discussions around a new stadium.

Wherever the Seahawks end up, proceeds from any sale will likely give a massive boost to Allen's already impressive philanthropic legacy.

That includes the new Fund for Science and Technology, which launched in August with plans to fund at least $500 million in grants over the next several years for “transformational science and technology” in the areas of bioscience, the environment and artificial intelligence.

Media reports put the fund’s total endowment at $3.1 billion.

"His estate is already one of the biggest philanthropies around," said Inside Philanthropy's Callahan, adding that he expects that impact to grow substantially as the estate continues to liquidate assets.

If most of the estate sales proceeds ultimately wind up in Allen's philanthropic organizations, it would could collectively amount to one of the largest philanthropic forces in the United States, Callahan said.

The Ford Foundation has assets of $16 billion, he said. "So if all that $20 billion ends up in one place, it would be one of the biggest foundations in America."

For recipients, the timing couldn't be better, given recent trends in reduced federal funding for the science-based research that Allen was so enthusiastic about, Callahan said.

Allen's focus on the life sciences is especially important, Callahan said, because "that area has been whacked by federal funding cuts.

©2026 The Seattle Times. Visit seattletimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments